|

Excerpts from The New York Times-Science Forum Remedios Varo, considered one of the greatest surrealist painters of the 20th century, is so obscure to most Americans that when Dr. Alan Friedman, a physicist and director of the New York Hall of Science,came across mention of her in a Thomas Pynchon novel years ago,a colleague assured him that Pynchon had made her up. An exhibition of Varo's art at the National Museum of Women

in the Arts includes

In "Harmony," the distinctly androgynous scientist is seeking to create a "theory of everything," using a musical staff, as an organizing device. The scientist strings onto the staff vegetables, animals, stones, pyramids, a scrap of paper with pi written out to six digits. Projecting from a wall near the staff, the hand of chance, an essential ingredient in scientific success, is helping the scientist by adding ingredients to the composition in progress. Her extravagantly meticulous and multivalent paintings have long been celebrated in Mexico, her adopted home, and now, 37 years after her death, Ms. Varo is at last beginning to receive international acclaim, including the admiration of a cadre not always known for its arthouse savvy: the scientific community. In a symposium at the National Museum for Women in the Arts, Dr. Friedman discussed the appeal Ms. Varo holds for scientists and engineers. He described how the artist metaphorically conveyed in her paintings some of the most revolutionary and complex scientific theories of the age, from Einstein's special theory of relativity and Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection to the premise that humans are the stuff of stars, their bodies built of elements baked in solar bellies millions or billions of years ago. "How many paintings have the square root of minus one in them?" he asked rhetorically in an interview. "Clearly she's fascinated by science. Her paintings include lots of machinery, gears and pulleys and cranks, test tubes and orreries," mechanical models of the solar system. One of the first textbooks about general relativity,"The Riddle of Gravitation," by Peter Bergmann, displayed one of Varo's paintings, "The Phenomenon of Weightlessness," on its cover. Varo sought in particular to convey the most profound and

creative moments in a scientist's life, when the researcher first dares

to imagine an alternate universe, a model of how things work that differs

radically from the models preceding it. "What she's doing, uniquely among

artists, is presenting this core moment of discovery that's so exciting

in science,she realized that this central act of the imagination in science,

this free play of the mind, is very similar to what artists do." For example,

in

A man, presumably a scientist, stands in a room with a number of orreries on shelves. One orrery, of the Earth and Moon, has broken free of its base and floats in the air. In addition, the room is duplicated and shown superimposed over the original, but at an angle of 30 degrees. This room is the special theory of relativity made real, or surreal. To depict the so-called Lorentz equations, which are at the heart of Einstein's revelation, one would draw a standard graph with X and Y axes, and then rotate the graph 30 degrees to show how time and space shift for different states of motion. The scientist is described as looking frightened, because the world is shifting under his feet,but in fact he's absolutely engrossed with every fiber of his being. This isn't something that happened to him; he invented it. He sees that there is another way of treating gravitation, and he's astonished that he's come up with the idea. He's also a little fearful, because you can never be sure your idea will be right, but this is his own creation he's dealing with. The figure in "Phenomenon" even has wild Einsteinian hair, still youthfully brown, for Einstein was only in his 20's when he conceived of special relativity. Born in Spain in 1908, Ms. Varo came by her interest in science patrilineally. Her father was a hydraulic engineer who encouraged his daughter's early display of artistic talent but drilled her in the rigors of draftsmanship and the correct use of the rule, carpenter's square and triangle. She studied art in Spain and France and became immersed in the Surrealism movement. Fleeing the Fascists and the Nazis, she found her way to Mexico, where she married Walter Gruen, an Austrian emigre who made a small fortune and told her, "If you want, all you have to do is paint." Paint is what she did, creating large, intricate canvases using a brush with only three bristles. Ms. Varo was an avid reader of science fiction and respectable popularizers of science like Fred Hoyle and Isaac Asimov. From thim she learned about cosmology, evolution and genetics. In one painting,

The musician can be seen as a stand-in for Charles Darwin, who is constructing a tower; the theory of evolution ; from stones containing fossils of ancient trilobites, fish, ferns,and spiral ammonites. Music to Ms. Varo served as an organizing principle, and so it is that strands from the flute are helping to array the fossil record into the mighty tower of evolution. Varo's most scientifically ambitious painting is

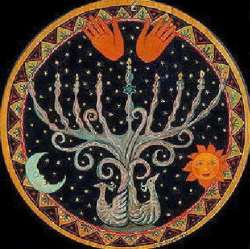

A woman with the feathers and face of an owl in one hand wields a paintbrush that extends from a violin hanging where her heart should be. In her other hand she holds a magnifying glass that refracts light from a star onto the page where her bird-in-progress is about to fly away. A Rube Goldberg-type apparatus collects stardust from another window and transforms it into the red, yellow and blue pigments from which the bird is drawn. Here, Ms. Varo portrays the three ingredients necessary for the origin of life: matter, made up of complex molecules that scientists have determined were formed by stellar fusion, deep in the interiors of stars, thus her stardust becomes paint pigment; energy, again the gift of suns, beaming from the star through the magnifying glass and onto the page; and organization, the anti-entropy principle, represented by the Owl Woman's cardio-violin. Thus, through Ms. Varo's profound artistry, the origin of life is transformed, so that it can be seen for what it is: a warm-blooded miracle, a song taking flight.

|